“Football no longer has a relationship with suffering. It’s probably why there are so few epic figures…”

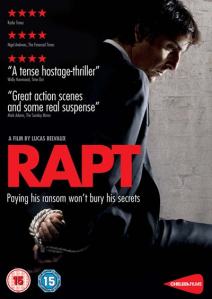

Lucas Belvaux is Belgian born film director working in France whose most renowned works to date are The Right of the Weakest (2005) and Rapt (2009). He is interviewed here on the release of his most recent film, 38 Witnesses (38 Témoins), which is about the murder of Kitty Genovese and is yet to be released in the UK.

You were born in Belgium but have lived in France for 30 years. Is yours a football of the North and its red bricks?

Actually my introduction to sport came through cycling. I used to ride a lot and in primary school we used watch the riders racing by every Wednesday. It’s a mythological sport, cycling. These guys who go out alone each morning, who push themselves -sometimes to their very limits. There’s a strong sacrificial aspect, the men of labour, farmers or mechanics who meet on the weekend ready to suffer, to work. In my opinion football no longer has this relationship with suffering. It’s probably why there are so few epic figures in football compared to cycling, apart from the big names of the ’60s and ’70s of course, like Best or Rocheteau. Football is a game about tactics and discontinuity but it’s rare that you see much self-sacrifice. Or maybe, at Barcelona. I liked the French team in 1998 as well. It was maybe the first time in the history of French football that there was the idea- an idea which lives on to this day, by the way- of us against the world. I think the press were probably less hostile than they thought but it was more than they could take, and it brought them together.

Although in South Africa in 2010 it was quite the opposite, it left them divided.

It’s very strange, what happened in Knysna. Extremely sad. Playing at the World Cup is supposed to be one of the biggest moments in the career of a footballer. I mean, becoming a footballer in the first place is a struggle, then you have to be selected to play for your country, which is extraordinary, plus then, you have to have qualified for the finals, so to be in this situation where there’s the possibility of reaching the final and suddenly everything falls apart is just unbelievable. Knysna is a story about 23 guys who no longer enjoyed playing together. How nobody managed to talk them round I’ll never know. You begin to appreciate, in hindsight, the strength of Aimé Jacquet; Blanc, Deschamps, Zidane, Thuram – they were maybe even harder to manage than the guys on the bus, but he led them towards this collective ecstasy. It’s something that really interests me because as a director a big part of your job is making sure everyone gets on. I’ve got to have an efficient squad; an actor who comes in only for one day has to be able to rely on a welcoming team. If I find out such and such has got too big an ego, I’d rather work with someone else.

How can we compare the role of an actor to that of a footballer?

Actors have a lot to learn from sportsmen; about concentration, solitude, the importance of the moment, your role within a team… I always ask my actors to express the least amount possible -it’s more mysterious, more profound. Take Zidane. He’s a pistolero, he’s Yul Brynner in The Magnificent Seven when he catches the gun without anyone knowing how… Cruyff had it too. Watching the great players, you often get the impression that they’re somehow not located exactly where they appear to be, that the threat that they pose isn’t manifest where they actually are. The real threat is the guy they set free, the way they can destroy the balance of the game. When you see Zidane or Pastore with their heads up, not looking at their feet but straight ahead with the heightened awareness of an animal in the jungle, like an antelope… At the moment when they finally strike at goal, they’re already three seconds ahead of our time. It’s really beautiful.

Can we compare the relationship between a director and his actor to that between a manager and his star player?

Working with Yvan Attal on Rapt, I could see certain real, individual qualities in his performance that convinced me of his potential to be something unique. It’s probably like how Thierry Henry would not have been the same player without Arsène Wenger. Another example right now is with Benzema and Mourinho at Madrid; you can tell that the penny’s dropped, and that’s because of Mourinho and this work that you don’t see.

After Liège and the setting for The Right of the Weakest, you’ve most recently been filming in Le Havre. Two football towns…

In Liège, footballers used to retire, buy a bar and settle down, but since they closed the factories it’s gone to pot. Liège is a strange city, a former minister was shot dead there [Andre Cools in 1991]… Of course, Charleroi’s in an even worse state, what with the Dutroux case [Paedophile and serial killer whose protracted prosecution brought about the resignation of the Justice Minister and Chief of Police]… Le Havre and Liège share a very strong visual power, a crazy energy. Le Havre is at the centre of globalisation, by the way, they do a lot of business with the Chinese.

Last Question: Is Eden Hazard, who plays in France, truly Belgian?

The question could be whether we can really consider any player as being from one country alone; there’s such an enormous transfer of information as well as of players between nations, there’s the exchange of staff between training centres, then there’s the television and the internet… The only place that’s different is possibly South America, where the football of the street still exists. Those who play over there on ruined pitches covered in broken glass will forever have a unique sense of space.

This interview appeared in So Foot #95 in April 2012 and was conducted by Brieux Férat.